Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study (VFSS)

The videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS), also known as the modified barium swallow study, is a radiographic procedure that provides a direct, dynamic view of oral, pharyngeal, and upper esophageal function (Logemann, 1986). A VFSS is typically conducted in a hospital by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) and radiologist. The patient is given various consistencies of food and liquid mixed with barium (or other contrast material), which allows the bolus to be visualized in real time on an X-ray during the swallow. The VFSS is beneficial in identifying whether aspiration has occurred. The VFSS is also used to determine the presence, timing and amount of aspiration as well to assess the anatomy and pathophysiology of oropharyngeal swallow function. The VFSS can also be used to gather information on the influence of compensatory strategies. This information is clinically useful in the development of a treatment plan (Martin-Harris et al., 2000).

VFSSs are typically performed with both an SLP and a radiologist present, allowing for professional collaboration. See ASHA’s resource on Interprofessional Education/Interprofessional Practice (IPE/IPP), and ASHA's Code of Ethics for further information regarding decision making related to professional conduct. Currently, there is no general national payer policy regarding the presence of the radiologist for VFSSs. However, some local Medicare Administrative Contractors, state regulatory agencies for radiology procedures, or third-party payers may require a radiologist’s presence during a VFSS. Please also see ASHA’s resource on State Instrumental Assessment Requirements for further information. During the procedure, the SLP assesses and documents swallowing physiology and function only, whereas the physician makes medical diagnoses (e.g., reflux, presence of a tumor). The SLP’s VFSS assessment and report do not include medical diagnoses based on the findings of the examination. The SLP should be aware of state, legal, and regulatory issues regarding the presence of a radiologist or other physician—as well as third-party payer requirements specific to the patient’s insurance carrier.

A VFSS is indicated when there is

- a need to observe oral preparatory, oral transit, pharyngeal, and/or esophageal phases of swallowing;

- a diagnosed or suspected presence of abnormalities in the anatomy of nasal, oral, pharyngeal, or upper esophageal structures that would preclude endoscopic evaluations;

- an aversion to having an endoscope inserted;

- the presence of a respiratory disorder;

- the presence of a persistent feeding refusal problem for which a swallowing disorder might be a contributing cause; or

- the need to determine treatment or management strategies to minimize the risk of aspiration and increase swallow efficiency (Arvedson & Lefton-Greif, 1998).

Additionally, a VFSS may be indicated in the pediatric population in the following situations:

- self-limiting behaviors during bottle feeding or breastfeeding

- failure to thrive

- unexplained febrile events

- frequent brief resolved unexplained events—sudden respiratory symptoms, change in responsiveness, change in muscle tone, or change in color

Contraindications to VFSSs include the following:

- Patient is unable to maintain adequate positioning.

- Patient’s size and/or posture prevents adequate imaging or exceeds limit of positioning devices.

- Patient has an allergy to barium and/or other contrast media (e.g., iohexol).

- Patient does not demonstrate a swallow response.

- Patient has a fistula (e.g., tracheoesophageal fistula).

- Patient is too medically unstable to tolerate the procedure.

- Patient is unable to cooperate or participate in an instrumental examination.

Special attention should be paid to radiation exposure. See ASHA’s resource on Radiation Safety for further information. Additional information regarding equipment, radiologic care, and the roles within the radiology department is also available from the American College of Radiology’s Practice Parameter for the Performance of the Modified Barium Swallow [PDF].

Procedure

Procedures for the VFSS may vary across settings and across clinicians. Clinicians should follow facility protocols for VFSSs. The SLP may prepare the patient for a VFSS as follows:

- Educate the patient and/or caregiver regarding VFSS procedures, radiation safety, and rationale for the examination.

- Position the patient upright, if possible.

- Use postural supports (e.g., head, trunk) as necessary.

- If the fully upright position is impossible, then the SLP may position the patient in their typical eating position.

- Consider having the patient fed by a familiar family member or caregiver, if possible (particularly if the patient is a child).

- Make every effort to maintain the patient in a calm, alert state during testing.

Once the VFSS begins, the SLP may

- identify relevant anatomical structures;

- evaluate the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing;

- identify the effectiveness of swallow function and probe sensory awareness;

- assess the effectiveness of altering bolus delivery or bolus consistency;

- consider alternative methods of presentation (e.g., modified cups, spoons, alternative nipple to modify flow rate);

- assess the effectiveness of compensatory techniques on swallow function; and/or

- assess the presence and effectiveness of the patient’s response to laryngeal penetration, residue, and/or aspiration.

Lateral and anterior–posterior views of the oral cavity, pharynx, and upper esophagus provide different valuable information on swallowing anatomy and physiology. Clinicians select bolus type (e.g., consistency, volume) for each trial carefully, as some consistencies and/or volumes may influence the clinician’s overall impression of the swallow function more than others (Martin-Harris et al., 2008; Sandidge, 2009). Clinicians may also instruct a swallow to allow the observation of any differences in swallow function between (a) when the patient is instructed to swallow and (b) when the patient spontaneously swallows. Clinicians also evaluate the influence of the method and rate of presentations, such as when the patient is fed by an examiner, when the patient is self-fed, when the patient is fed by a caregiver, or when solids and liquids are alternated. A complete VFSS requires a sufficient number of swallowing attempts to determine the need for additional assessments and interventions through interprofessional team referral(s) as well as to make recommendations concerning

- exercises and maneuvers to improve swallowing function based on observed anatomical and physiological impairment,

- compensatory techniques to improve safety and efficiency while consuming an oral diet,

- the most safe and efficient oral diet consistencies, and

- the possible need for alternate nutrition and hydration (Logemann et al., 2008).

Clinicians also note the individual’s tolerance of and response to the examination (e.g., following directions, fatigue, signs of stress in medically complex patients, ability to repeat therapeutic interventions). Indications of an adverse reaction to the procedure may include—but are not limited to—agitation; changes in breathing pattern; changes in alertness; changes in coloring; nausea and vomiting; and/or changes in overall medical status, which may be assessed via the pulse oximeter, heart rate monitor, and so forth.

Given the speed and the dynamic nature of swallow function, it is beneficial for the SLP to record these studies and review the recording using standardized measurements (i.e., pharyngeal constriction ratio, Normalized Residue Ratio Scale) as well as by applying a frame-by-frame analysis of kinematic and temporal events (Lee et al., 2017; Leonard et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2020; Molfenter & Steele, 2011, 2012, 2013; Pearson et al., 2013; Vose et al., 2018).

Anatomical Structures

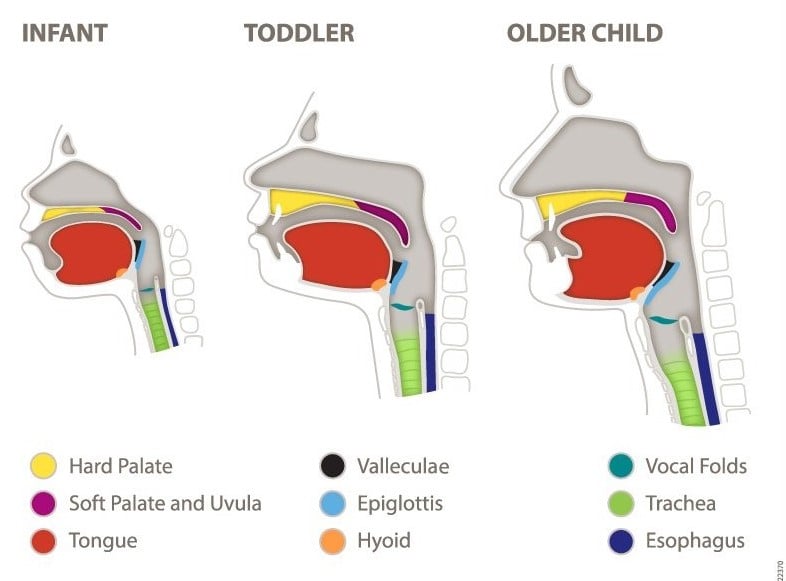

During the VFSS or review of the recording, clinicians identify the anatomical structures (as illustrated below), including any anatomical and/or physiological abnormalities. For observations during a VFSS, see table below.

Image 1: Anatomical Structures

Observations From VFSS

| Lip closure | Patient’s ability to approximate top and bottom lips |

| Tongue control | Volitional and controlled lingual movement |

| Bolus preparation | Patient’s ability to create a well-contained bolus |

| Bolus transport | Patient’s ability to move the bolus from the oral cavity to the pharyngeal cavity |

| Oral residue | Remaining residue in the oral cavity following oral transport |

| Initiation of the pharyngeal swallow response | Head of the bolus at the initiation of the pharyngeal swallow (hyoid burst) response |

| Soft palate elevation | Upward movement of the soft palate to create velopharyngeal closure |

| Laryngeal elevation | Extent and timeliness of upward movement of the larynx during the swallow |

| Anterior hyoid motion | Extent and timeliness of forward movement of the hyoid |

| Epiglottic movement | Extent and timeliness of passive epiglottic inversion to meet with the arytenoids (moving anteriorly and superiorly) |

| Laryngeal closure | Medial movement of the larynx observed at the vocal folds; may be able to observe only from the anterior–posterior view |

| Pharyngeal stripping wave | Contraction of the posterior pharyngeal wall from the top moving downward |

| Pharyngeal contraction | Approximation of the pharyngeal walls |

| Pharyngeal esophageal sphincter opening | Opening of the pharyngeal esophageal sphincter to allow the bolus to move from the pharynx to the esophagus |

| Tongue base retraction | Posterior movement of the tongue base to make contact with the posterior pharyngeal wall |

| Pharyngeal residue | Remaining residue in the pharynx following the pharyngeal swallow |

| Esophageal clearance in upright position | General observation of the passage of the bolus through the esophagus |

Penetration and Aspiration During the VFSS

Assessment and diagnosis via the VFSS requires clinicians to record pathophysiology that leads to episodes of atypical levels of penetration and aspiration during a VFSS. Doing so may help suggest interventions that may mitigate negative outcomes and help plan for treatment. Episodes of penetration and/or aspiration can occur before, during, or after the swallow. The Penetration–Aspiration Scale (Rosenbek et al., 1996) is an 8-point scale used to describe penetration and aspiration events. The clinician observes the bolus and the patient’s response to the bolus, including the following scenarios (Rosenbek et al., 1996):

- if the bolus enters the airway—and, if so, at what level and how much

- if the patient attempts to clear a penetrated or aspirated bolus from the airway

- if the patient is successful in ejecting the bolus from the airway (if clearing is attempted)

Radiographic Imaging Settings

Radiographic imaging settings are determined by the radiologist administrating the assessment. Either a continuous fluoroscopy rate or a fluoroscopic pulse rate (FPR) of 30 pulses per second is preferred for VFSS (Martin-Harris et al., 2020, 2021; Peladeau-Pigeon & Steele, 2013). FPR may decrease radiation exposure from that of continuous rate. However, decreasing FPR below 30 can limit accurate visualization of the anatomy and physiology of swallowing. Lower FPR means fewer available images for assessment. Low FPR may influence clinician recommendations and judgment of swallowing impairment and findings during the assessment (Bonilha, Blair, et al., 2013). Clinicians should also be aware of the following:

Instrumentation used by their facility. Modern and technologically advanced fluoroscopes may provide clearer images than older instruments.

Image compression is frequently used to decrease file size of VFSS recordings. This is common in digital systems. Heavily compressed images may lose resolution or other characteristics and may limit a clinician’s ability to accurately assess swallowing function.

Recording software can impact the quality of a VFSS image. For example, if recording software captures at a rate of 15 frames per second (FPS) and the VFSS is set to 30 FPR, there is a net loss of 15 FPS (i.e., FPR minus FPS).

Playback device features, such as the settings and quality of the computer and/or monitor’s software and hardware, influence a clinician’s interpretation. Clinicians should optimize their computer’s resolution and display settings (e.g., contrast, brightness) to provide the most accurate image.

There are other factors regarding instrumentation that are not described in this document. See Peladeau-Pigeon & Steele (2013) for further information.

Limitations of the VFSS

Limitations of the VFSS include the following:

- Time constraints due to radiation exposure. Please see ASHA’s resource on Radiation Safety for further information.

- A limited sample of swallow function that may not be an accurate representation of typical mealtime function.

- Challenges in visualizing the swallow due to poor contrast.

- Challenges in representing food typically eaten by a patient.

- Limited evaluation of the effect of fatigue on swallowing.

- Refusal of the bolus, as barium is an unnatural food source and is not tolerated by some patients (Logemann, 1998).

- Positioning may not be optimal.

- Fluoroscopy time parameters.

- Severe oral aversive behaviors that limit oral intake during an examination.

SLPs follow universal precautions and facility procedures for infection control (e.g., adequate disinfection of equipment). Decontamination, cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization of multiple-use equipment before reuse are carried out according to facility-specific infection control policies and services and according to manufacturers’ instructions. All equipment is used and maintained in accordance with the manufacturers’ specifications. For further information on infection control, please visit ASHA’s page on infection control resources for audiologists and speech-language pathologists. Please see the Resources section below for further materials.

Resources

- ASHA's Aerosol Generating Procedures

- Dysphagia Competency Verification Tool (DCVT): User's Guide [PDF]

- Coronavirus/COVID-19 Updates

- Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES)

- Scaling the swallow: The Penetration–Aspiration Scale

- State Instrumental Assessment Requirements

References

Arvedson, J. C., & Lefton-Greif, M. A. (1998). Pediatric videofluoroscopic swallow studies: A professional manual with caregiver guidelines. Communication Skill Builders.

Bonilha, H. S., Blair, J., Carnes, B., Huda, W., Humphries, K., McGrattan, K., Michel, Y., & Martin-Harris, B. (2013). Preliminary investigation of the effect of pulse rate on judgments of swallowing impairment and treatment recommendations. Dysphagia, 28(4), 528–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-013-9463-z

Lee, J. W., Randall, D. R., Evangelista, L. M., Kuhn, M. A., & Belafsky, P. C. (2017). Subjective assessment of videofluoroscopic swallow studies. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 156(5), 901–905. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599817691276

Leonard, R., Belafsky, P. C., & Rees, C. J. (2006). Relationship between fluoroscopic and manometric measures of pharyngeal constriction: The pharyngeal constriction ratio. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 115(12), 897–901. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940611501207

Logemann, J. A. (1986). Manual for the videofluorographic study of swallowing. Little, Brown.

Logemann, J. A. (1998). Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders (2nd ed.). Pro-Ed.

Logemann, J. A., Rademaker, A., Pauloski, B. R., Antinoja, J., Bacon, M., Bernstein, M., Gaziano, J., Grande, B., Kelchner, L., Kelly, A., Klaben, B., Lundy, D., Newman, L., Santa, D., Stachowiak, L., Stangl-McBreen, C., Atkinson, C., Bassani, H., Czapla, M., . . . Veis, S. (2008). What information do clinicians use in recommending oral versus nonoral feeding in oropharyngeal dysphagic patients? Dysphagia, 23(4), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-008-9152-5

Martin-Harris, B., Bonilha, H. S., Brodsky, M. B., Francis, D. O., Fynes, M. M., Martino, R., O’Rourke, A. K., Rogus-Pulia, N. M., Spinazzi, N. A., & Zazour, J. (2021). The modified barium swallow study for oropharyngeal dysphagia: Recommendations from an interdisciplinary expert panel. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 6(3), 610-619. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_PERSP-20-00303

Martin-Harris, B., Brodsky, M. B., Michel, Y., Castell, D. O., Schleicher, M., Sandidge, J., Maxwell, R., & Blair, J. (2008). MBS measurement tool for swallow impairment—MBSImp: Establishing a standard. Dysphagia, 23(4), 392–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-008-9185-9

Martin-Harris, B., Canon, C. L., Bonilha, H. S., Murray, J., Davidson, K., & Lefton-Greif, M. A. (2020). Best practices in modified barium swallow studies. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(2S), 1078-1093. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00189

Martin-Harris, B., Logemann, J. A., McMahon, S., Schleicher, M., & Sandidge, J. (2000). Clinical utility of the modified barium swallow. Dysphagia, 15(3), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004550010015

Miller, M., Vose, A., Rivet, A., Smith-Sherry, M., & Humbert, I. (2020). Validation of the normalized laryngeal constriction ratio in normal and disordered swallowing. The Laryngoscope, 130(4), E190–E198. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28161

Molfenter, S. M., & Steele, C. M. (2011). Physiological variability in the deglutition literature: Hyoid and laryngeal kinematics. Dysphagia, 26(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-010-9309-x

Molfenter, S. M., & Steele, C. M. (2012). Temporal variability in the deglutition literature. Dysphagia, 27(2), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-012-9397-x

Molfenter, S. M., & Steele, C. M. (2013). Variation in temporal measures of swallowing: Sex and volume effects. Dysphagia, 28(2), 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-012-9437-6

Pearson, W. G., Molfenter, S. M., Smith, Z. M., & Steele, C. M. (2013). Image-based measurement of post-swallow residue: The Normalized Residue Ratio Scale. Dysphagia, 28(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-012-9426-9

Peladeau-Pigeon, M. & Steele, C. M. (2013). Technical aspects of a videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 37(3), 216-226.

Rosenbek, J. C., Robbins, J. A., Roecker, E. B., Coyle, J. L., & Wood, J. L. (1996). A Penetration–Aspiration Scale. Dysphagia, 11(2), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00417897

Sandidge, J. (2009). The Modified Barium Swallow Impairment Profile (MBSImp): A new standard physiologic approach to swallowing assessment and targeted treatment. Perspectives on Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia), 18(4), 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1044/sasd18.4.117

Vose, A. K., Kesneck, S., Sunday, K., Plowman, E., & Humbert, I. (2018). A survey of clinician decision making when identifying swallowing impairments and determining treatment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(11), 2735–2756. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-S-17-0212